Category Archives: dryland

Shoulder Stability and Functional Dryland – Insights From Institute of Human Performance

Another Fabulous DVD by Grif Fig and JC Santana: Shoulder Exercises for Swimmers

Another Fabulous DVD by Grif Fig and JC Santana: Shoulder Exercises for Swimmers

Prehabilitation, Rehabilitation, and Elite Performance Shoulder Training. Educate your coaching staff and team on the training methods that have kept shoulders healthy at the world renowned Institute of Human Performance for years.

Laminated 8 page exercise guide included. Product # 718member price $40 + shipping. Click HERE to order now.

Grif and JC’s other DVD is Laps – Functional Dryland Training for Swimmers

Grif Fig and Juan Carlos Santana bring you over 50 years of performance enhancement training specifically applied to the sport of swimming. Now you can see the philosophy, training methods and exercises that are used at the world renowned (IHP) to develop world class swimmers of all ages. If you are a swim coach or a personal trainer working with swimmers, this DVD will teach you the latest training methods used at IHP that can take your athletes to the next level.

Product #705 Member price $30.00 +shipping. Click HERE to order now.

Strength Training for Swimmers: An Integrated and Advanced Approach

The purpose of this article is to discuss the benefits of strength training and the factors that need to be considered when designing a program for a competitive swimmer. We will also discuss a functional approach to strength training and show you how it can be incorporated with a more traditional approach. IHPSWIM’s philosophy is that each style of training has its benefits and therefore should be integrated together. This article will conclude with an example of one our daily strength programs.

Strength training provides far too many benefits to simply just throw together a program full of random exercises with no rhyme or reason. Just as swim coaches plan, periodize, and vary intensity and volume, the same should be done for their strength program. With a well designed strength program athletes will see great improvements in strength, power, an increase in muscle mass (if desired), core strength, and most importantly you will see less overuse injuries. Overuse injuries tend to happen because of muscle imbalances. A good strength program will include exercises that address these imbalances as well.

For the purpose of this article, let’s first start by defining what traditional lifts are. These are your standard barbell squats, bench press, lat pull down and machine exercises (ie. Nautilus) that are more oriented towards muscle isolation, a fixed range of motion and single plane movement. These types of exercises are great for developing growth in lean muscle tissue and increasing strength and power. What they lack is the ability to increase core strength and are restrictive when it comes to performing exercises that include multi-limb and multi-directional movement. Exercises that are multi-limb and multi directional in nature and movement oriented have been labeled “functional training” by some of the leaders in the fitness industry. This type of training is based on the idea of training movements (multiple muscle groups working together as a unit) and not isolated muscle groups. Integrating traditional and functional exercises into a strength program provides the benefits from each approach. The obstacle that coaches may face is getting all of this in with only a limited amount of time set aside for training done out of the water. The sample workout in this article will demonstrate a very easy way to make this work.

Shown below is an example of an upper body power phase workout when training in the weight room 2 days a week. Day # 1 focuses on upper body power and Day #2 focuses on the lower body power (not shown). Every workout contains a traditional, functional, core and rotational exercises.

The power phase typically lasts 4 weeks but can vary depending on other variables. Please note that the power phase is only done after a general conditioning/hypertrophy phase (high volume, low to moderate intensity) and a strength phase (low volume, high intensity) are performed at some point in almost all cases.

The first circuit on Tuesday starts off with the Lat pulldown. Perform 5 reps and then take a 45 second rest period followed by 5 medicine ball slams. This combination is a version of complex training, a type of strength training that is used to develop power. Every circuit will start with a variation of this combination which is a traditional lift followed by an explosive movement (after a 45 second rest) that is similar to the movements and muscle groups performed in the traditional lift. The 3rd exercise is the diagonal cable chop (Figure 1) which is a great exercise for the strengthening rotation in the core. The 3rd exercise represents a functional or core exercise. This circuit will be repeated 3 times.

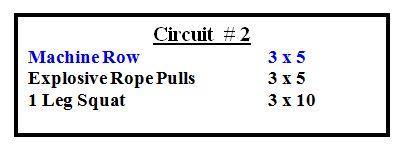

The 2nd circuit of the day starts with a traditional machine row followed by an explosive recline rope pull (Figure 2). We use a very thick rope that is looped over monkey bars. This movement needs to be fast and should result in there being slack in the rope at the top of the exercise. This is followed by a 1 legged squat which is great for developing leg strength, hip stability and requires no equipment. Progress this exercise by increasing the range of motion, as long as control and proper technique can be maintained throughout. Never perform exercises that are out of control and sloppy.

The 3rd and final circuit of the day begins with a 1 arm Dumbbell Row. After the 45 second rest period an explosive pull – up is performed. The objective here is to perform a fast pull – up and slightly catch air. The regular pull up MUST be mastered before doing this. This is a very advanced exercise and should only be performed by athletes that have above average pulling strength and no shoulder problems. The 3rd exercise is the T – stabilization push – up which can be performed on an incline if to difficult to perform properly on the ground. This exercise is a great core and shoulder stabilization exercise.

At the end of all 3 circuits we usually do 3 fast rope climbs for time. Depending on the level of strength, we can perform this with the assistance of the legs, no legs, and finally the hardest version, which is starting from the seated position off of the floor.

There is no one style of training that is the end all be all. Limiting yourself to only doing traditional exercises or only doing functional exercises is limiting the potential of you and your athletes. These circuits make it easy to integrate everything together and get the best of the different training methods out there. Our goal at IHPSWIM is to help swimmers and coaches organize and implement a solid strength and dryland program.

For more information on our training philosophy check out our DVD titled LAPS:Functional Dryland Training for Swimmers or email Grif at Grif@ihpfit.com. I hope this article will help you meet your goals and get you the results you want!

Flexibility: The What, Why, and How

Many coaches and athletes perform static stretching because they believe it necessary. Many do not take the time to ask questions about how relevant it is to athletic performance. I believe that after this article you will be asking a lot of questions about how static flexibility should be used. – Grif Fig

Flexibility: The What, Why, and How

by

JC Santana, MEd, CSCS

One of the most controversial topics in fitness is flexibility. Many personal trainers consider flexibility and stretching to be synonymous, and thus include some for of stretching exercises in their workout programs because they have always heard it is the right thing to do. One of the most popular forms of stretching is static stretching. Whether it is performed pre or post workout, static stretching is the most common form of flexibility training. If one performs a Medline search for “flexibility” related research, the search will provide a plethora of conflicting studies on stretching and flexibility. Field observations may also be equally diverse in their findings. In spite of this diversity in theory, many educational organizations and trainers still espouse to static stretching when it comes to enhancing flexibility.

Flexibility is generally defined as “the range of motion about a joint” (1). There is no doubt that healthy movement and proper range of motion (ROM) are necessary for normal function and optimum performance. However, the question still remains, what is healthy and proper? If one references any anatomy or rehabilitation textbook, one will find anatomical ROMs assigned to all joints of the body. These ROMs are labeled “normal” and serve as references. Traditional fitness and rehabilitation programs have been guided by these ROMs in order to provide “optimum” function. However, applying this traditional approach allows a few very important concepts to be overlooked.

In order to provide some clarity to this discussion, we have to ask some important questions.

1) Why are we stretching?

2) Is flexibility related to injury prevention?

3) Is the passive ROM (developed through static stretching) related to active ROM? OR – just because a can get 140 degrees of static (passive) ROM out of a joint, will the body provide that same range at high speeds and loads (i.e. during a functional task)?

4) Is it healthy to statically develop a ROM that can’t be controlled at functional speeds and loads? Is there a difference between anatomical ROM and functional ROM?

5) Can we get flexibility through other methods of training outside of conventional stretching techniques?

6) Which flexibility do I really need the most of in functional daily activities (FDAs) and sports, static or dynamic, anatomical or functional?

All of these questions are valid and deserve some attention. However, getting to the absolute truth behind each question may be a different story. Since any position on flexibility can be supported by some research, we would like to keep the discussion based on our observations, coaching experience and common sense. I believe a simplified discussion will allow one to see flexibility from a more holistic perspective.

Most trainers stretch to gain flexibility. There is no doubt that flexibility is important, we just don’t know how important it is. The research from the armed-forces illustrates that the most and least flexible recruits are the most injured during boot-camp.(5) Furthermore, all of the research reviews that have looked at stretching and injury prevention show no correlation between the two. According to this body of work, more flexibility and stretching before an event does NOT protect one from injury.

Another aspect of flexibility one has to look at is the difference between passive flexibility (i.e. stretching) and active flexibility (i.e. functional ROM). Working with many athletes, we have had the ability to see many different ways to develop and express flexibility. Not all are tied into static stretching. Based on our observations, static flexibility is not related to active ROM. That is – the body will give you more ROM when it does not need to control speed, tension and stabilization in the ROM. As an example, all of our fighers can exhibit more ROM through a controlled passive stretch than they can through a live kick, even when instructed to kick as high as possible. What does it mean to us? We interpret this as, “if you can’t stabilize and control ROM the body won’t allow you to use it.” Therefore, our clients warm-up dynamically and incorporate full ROM training into their strength programs. We feel our strength exercises move our clients through the ROMs they will encounter in their chosen activity. Some research even indicates that it is the total amount of time at a given ROM is the predominant factor in providing ROM, and not the time of each stretch. In practical terms, this could mean that 15 reps of a reaching lunge may provide the same hamstring ROM benefits as15 seconds of a sit and reach stretch. However, the reaching lunge would provide additional stability, balance, strength, caloric burn and coordination not derived from the sit a reach stretch. This approach to training develops all of the functional flexibility we need for health and elite performance. All of our warm-up and training protocols inherently develop active ROM and if extreme static ROM is needed (i.e. as with our wrestlers), we make it part of our warm-up; holding the extreme position for 5-10 seconds.

To illustrate exactly how we integrate flexibility into our strength training programs, we would like to share two of our favorite exercises: the reaching lunge (RL) and the T-Stabilization (T-Stab) push-up. Both exercises include a unique blend of strength and flexibility. Each can also be modified to match any application. The bottom position of the RL resembles a static hamstring stretch. It can be performed in all three planes of motion to address the multi-planar nature of functional ROM. The stance, speed and range of movement can be tailored to meet the specific capabilities and training goals of any individual. The RL can also emphasize any muscle group within the kinetic chain. For example, reducing knee and spinal flexion can increase the ROM demands of the hamstring. This concept of “isolated integration” was first coined by Gary Gray, the father of modern functional training.(2) Using dumbbells with the RL can provide an excellent combination of ROM and strength. The RL progression is a staple movement in our training model and, along with other exercise, is credited with our near-perfect record against hamstring injuries.

The T-Stab push-up is also one of our staple exercises that incorporate functional strength and flexibility training. It too looks like a chest stretch, accept with more versatility. Like the RL it can also be modified specific to the capabilities and goal of any individual. For example, the upper body support can be elevated (e.g. using a fixed barbell at about waist high) and the rotation reduced to attenuate the intensity of the movement. Conversely, a lower support position (i.e. floor), the use of a weighted vest and increased rotation can provide a more advance training stimulus.

It should be made clear we do not feel that static stretching is not effective or does not have a place in fitness and performance training. However, we have not been able to identify to what degree it is effective, if it is the most effective road to functional flexibility and performance, and where its exact place is in the training scheme. We certainly acknowledge it as a tool in the rehab setting. We can also accept it as a “feel good” modality and have no objections to it being used everyday for that purpose. We often roll on medicine balls and biofoam rollers for a few minutes prior to workouts for that reason; it loosens us up and makes us feel good. However, we do find it alarming when coaches and organization insist on static stretching as the “best” or “necessary” method of preparation, improving functional ROM and reducing injuries. We believe the best flexibility method is still an ideological figment.

In summary, our field observations clearly indicate that static muscle compliance and active muscle compliance are not related (i.e. muscle compliance is a big component of ROM). Our observations also indicate that active muscle compliance is more important to our fitness performance goals. Over the last decade we have combined dynamic flexibility into our strength movements and have basically removed all static flexibility from our day-to-day training. The results are without question; over 500 case studies show a better then 95% success rate against non-contact and overuse injuries in the absence of static stretching. This is not to be taken as the best way to train. It just illustrates that there may be many ways to do things right.

1) Baechle, T.R., Earle, R.W.(ed). Essentials of Strength and Conditioning. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2000.

2) Gray, G.W. Chain Reaction Festival Seminar. San Diego, Cal., Sept 1996.

7) Jones, S, B. H., and J. J. KNAPIK. Physical training and exercise-related injuries. Surveillance, research and injury prevention in military populations. Sports Med. 27:111-125, 1999.

8) Knudson, D. V., P. Magnusson, and M. Mchugh. Current issues in flexibility fitness. Pres. Council Phys. Fitness Sports 3:1-6, 2000.

9) Kokkonen, J., A. G. Nelson, and A. Cornwell. Acute muscle stretching inhibits maximal strength performance. Res Q. Exerc. Sport 69:411-415, 1998.

6) Pope, R. P., R. D. Herbert, J. D. Kirwan, and B. J. Graham. A randomized trial of preexercise stretching for prevention of lower-limb injury. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc., Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 271-277, 2000.

3) Santana, J.C. Flexibility: More is not necessarily better. NSCA Journal: 26(1). 2004.

4) Schiilling, B., Stone, M. Stretching: Acute Efects on Strength and Power Performance. NSCA Journal: 21(1). 44-47. 2004.

10) Shrier, I. Stretching Before Exercise Does Not Reduce the Risk of Local Muscle Injury: A Critical Review of the Clinical and Basic Science Literature. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 9:221-227. 1999.

5) Thacker, S. B., J. Gilchrist D. F. Stroup, and C. D. Kimsey, JR. The Impact of Stretching on Sports Injury Risk: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc., Vol. 36, No. 3, pp. 371-378, 2004.

EXERCISE VIDEO

Here is one of our favorite exercises for developing functional strength and flexibility. This reaching lunge protocol was designed by Gary Gray. Click below to see the video.

Ten Day Dryland Training Cycle – Some Thoughts from Coach John Leonard

Dryland Training Cycle

Dryland Training Cycle

This is a ten day cycle. On the 2nd ten day go-round, on the odd numbered days, add a heavier med ball to the routine. On the 2nd go round add WEIGHT to each exercise. Same on the 3rd go-round. Same on the 4th go-round. After 40 days of training like this, we should adjust the routine to incorporate some changes and new material. You’ll start out needing 30 minutes a day on the first couple of days, (outside of running, which can be done in the same session or at a different time of day. But it will rapidly increase to about 45 minutes/1 hour per day towards the end of each cycle because of the increase in numbers.

Probably good to take a 2-3 day Break from dryland at the end of each 10 day cycle.

JL

#1 – Run 30 minutes steady, easy

Med ball – standing – 25 chest passes, 25 overheads

Med ball – standing – 50 figure eights – change direction half way.

Med ball – “hikes” – 10 each partner.

Med ball situps – 4 x 25 sprint speed with ball.

Pushups – normal position – 3(10-9-8-7-6) 40 per set, 120 total.

Med ball wall throws – Overhead – 25, from side 25 left, 25 right, heavy ball.

#2 – Planks – 4 positions – 2 sets – 1 warmup 15 seconds, 1 full at 30 seconds.

Pushups with feet on med-ball – 10

Situps with feet on exercise ball – 30

Pullups – 5 x 5

Pulldowns with light weight on machine – 3×30

Dumbbell alternate arm flings – 30 each arm.

Bam-bams with med ball – 3 x 50

Swim Bench – 75 recovery strokes – Turned around backwards.

#3 – Run 30 minutes – 20 steady, 10 sprints.

Med ball – standing – 30 chest passes, overheads

Med ball – standing – 60 figure eights – change direction half way.

Med ball – “hikes” – 15 each partner.

Med ball situps – 5 x 25 sprint speed with ball.

Pushups – normal position – 4(10-9-8-7-6) 40 per set, 160 total.

Med ball wall throws – Overhead – 30, from side 30 left, 30 right, heavy ball.

#4. – Planks – 4 positions – 2 sets – 1 warmup 15 seconds, 1 full at 40 seconds.

Pushups with feet on med-ball – 15

Situps with feet on exercise ball – 40

Pullups – 5 x 6

Pulldowns with light weight on machine – 4×35

Dumbbell alternate arm flings – 40 each arm.

Bam-bams with med ball – 4 x 50

Swim Bench – 100 recovery strokes – Turned around backwards.

#5 – Run 30 minutes – 15 steady, 15 sprints

Med ball – standing – 40 chest passes, 40 overheads

Med ball – standing – 70 figure eights – change direction half way.

Med ball – “hikes” – 20 each partner.

Med ball situps – 6 x 25 sprint speed with ball. (125)

Pushups – normal position – 5(10-9-8-7-6) 40 per set, 200 total.

Med ball wall throws – Overhead – 350, from side 35 left, 35 right, heavy ball.

#6. Planks – 4 positions – 2 sets – 1 warmup 15 seconds, 1 full at 45 seconds.

Pushups with feet on med-ball – 20

Situps with feet on exercise ball – 50

Pullups – 5 x 7

Pulldowns with light weight on machine – 4×45

Dumbbell alternate arm flings – 50 each arm.

Bam-bams with med ball – 4 x 70

Swim Bench – 125 recovery strokes – Turned around backwards.

#7 – Run 40 minutes – Steady

Med ball – standing – 50 chest passes, 50 overheads

Med ball – standing – 70 figure eights – change direction half way.

Med ball – “hikes” – 25 each partner.

Med ball situps – 7 x 25 sprint speed with ball. (175)

Pushups – normal position – 6(10-9-8-7-6) 40 per set, 240 total.

Med ball wall throws – Overhead – 40, from side 40 left, 40 right, heavy ball.

#8. Planks – 4 positions – 2 sets – 1 warmup 15 seconds, 1 full at 50 seconds.

Pushups with feet on med-ball – 25

Situps with feet on exercise ball – 60

Pullups – 5 x 8

Pulldowns with light weight on machine – 4×50

Dumbbell alternate arm flings – 60 each arm.

Bam-bams with med ball – 4 x 80

Swim Bench – 2 x 75 recovery strokes – Turned around backwards.

#9 – Run 40 minutes – 20 steady, 15 sprint, 5 steady.

Med ball – standing – 60 chest passes, 60 overheads

Med ball – standing – 80 figure eights – change direction half way.

Med ball – “hikes” – 30 each partner.

Med ball situps – 8 x 25 sprint speed with ball. (200 )

Pushups – normal position – 7(10-9-8-7-6) 40 per set, 280 total.

Med ball wall throws – Overhead – 45, from side 45left, 45 right, heavy ball.

#10. Planks – 4 positions – 2 sets – 1 warmup 15 seconds, 1 full at 55 seconds.

Pushups with feet on med-ball – 30

Situps with feet on exercise ball – 70

Pullups – 5 x 9

Pulldowns with light weight on machine – 4×60

Dumbbell alternate arm flings – 70 each arm.

Bam-bams with med ball – 4 x 100

Swim Bench – 2 x 100 recovery strokes – Turned around backwards.

Dryland: Stronger Shoulders for $2 and 6 Minutes Per Day

Grif Fig, of IHPSWIM.com, recently posted a great article on shoulder stability and prehab exercises. Prehab – rather than rehab – is the coined term for sports injury prevention – i.e., make the body strong and mobile with functional and sport-specific exercises as a way to prevent overuse/overtraining injuries down the road.

Grif’s post shows a demo of these exercises using a flexibar. A similar piece of equipment is the Bodyblade. I don’t know much about the flexibar, but a Bodyblade will cost you somewhere between $50 and $150, depending on the weight/size you want.

Use is simple: You push and pull on the pipe (basically waving it back and forth), which produces the oscillation or flex of the pipe, which then require force output from you to neutralize the speed and movement of the blade. You have to start, stop and change directions of your own body while controlling your mass.

Your athletes can get the same effect – at a much cheaper cost – through the use of PVC pipe. Here’s what I’ve had my athletes do:

1. Go to Home Depot/Lowes/any sort of hardware store that sells PVC pipe.

2. Purchase 1/4 inch PVC pipe at a length somewhere between 7 and 8 feet (long enough to be flexible; short enough to be manageable). This will cost you less than $2.00.

3. Bring to practice. (Obviously, it’s much easier if you can store these at the pool, once acquired.)

4. Daily, incorporate a prehab routine into your practice. There are a multitude of routines you can follow, but I’ve had my athletes on a very simple plan that took us about six minutes per day.

– 30 secs left arm/30 secs right arm — arm extended overhead

– 30 secs left arm/30 secs right arm — arm extended in front of body

– 30 secs left arm/30 secs right arm — arm extended out to side – palm forward

– 30 secs left arm/30 secs right arm — arm extended out to side – palm down

The benefits are enormous – athletes increase core stability, shoulder stability and improve their overhead and lateral range of motion. And incorporating these exercises with some regularity and self-discipline really does prevent shoulder soreness, pain and injury.

So, if you want less whining and “stretching” on the wall, and/or stronger and healthier athletes with far less susceptibility to injury, start some shoulder prehab – all you need is $2 for PVC pipe and 6 minutes per day.

(Note: Although the shoulder prehab routine described above is a bit different from typical use of a Bodyblade, click here for a video if you need a little more insight as to how it all works.)

Build Better Athletes with ASCA’s New Dryland Course

Check out this new edition of ASCA’s popular Dryland Training School (Oct. 2010). This edition is almost 50% more extensive than the original school and has a number of new and useful features for coaches. First, it comes with a DVD with 110 minutes of extensive demonstrations of more than 100 dryland training exercises. Second, there are three chapters that fully develop the place of dryland training in all programs from young age group novice athletes, to the elite athlete. Third, it has a chapter that develops the idea of how we relate what we do on dryland, to direct faster swimming in the water. The course also has information on developing a ‘cookbook’ approach if you lack the time to spend on extensive dryland development, and still want to do some dryland training. And finally, there are five chapters that develop specific routines in different modalities such as stretch cords, Med-balls, Plyo-balls, hand weight exercises, and exercises with very limited amounts of equipment. Whether you coach Age Group Athletes or Senior Swimmers, this manual is your basic primer on what to do, when and how to do it, and what it takes to effectively improve the athleticism of your athletes.